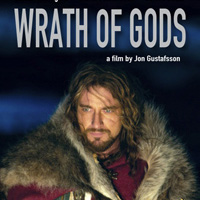

cultures merge

Iceland-born director brings

Anglo-Saxon epic to his homeland

by David Jón Fuller

Sturla Gunnarson is bringing an ancient hero to life in the wilds of Iceland. The Icelandic-Canadian filmmaker is helming a international production of Beowulf, starring Gerard Butler and Ingvar Sigurdsson. Beowulf, a poem written in Anglo-Saxon, is believed to be one of the oldest extant works of English literature. Ironically, none of its characters are English. The plot centres on the struggles of a Scandinavian warrior, Beowulf, against the monster Grendel.

“I have been wanting to do a story that has been tied to my tribal, my ancestral, past for a long time,” says Gunnarsson.“When I started to think about [Beowulf], it just seemed to be such a great fit for me, because while it’s written in the eighth century by Anglo-Saxons, it recounts events that take place in the sixth century in a pagan Norse country, so it’s about my ancestors.”

“There is a sort of integrity to doing the story in English. Somehow Beowulf, in the eighth century, becomes the place where my two cultures merge. Where my Norse tribal past and my adopted Anglo-Saxon culture merge in this one story.”

His attraction to the material isn’t just intellectual, though. “The appeal is that it’s a great story, it’s an example of the hero myth,” he says. “Every Western you’ve ever seen is based on Beowulf — so the story itself has tremendous bones, and it really appealed to me, the idea of doing something that was kind of a ‘scary’ movie.”

His attraction to the material isn’t just intellectual, though. “The appeal is that it’s a great story, it’s an example of the hero myth,” he says. “Every Western you’ve ever seen is based on Beowulf — so the story itself has tremendous bones, and it really appealed to me, the idea of doing something that was kind of a ‘scary’ movie.”

The film is a cooperative effort between Eurasia Motion Pictures (Canada) Spice Factory (U.K.), and Bjolfskvida (Iceland). The screenplay was written by Andrew Rai Berzins.“We’re doing Beowulf and Grendel; we’re doing the first half of the story,” says Gunnarsson. “And we’re not illustrating the myth in the same way that the Lord of the Rings [movie trilogy] does. This is not an illustration of the myth that Beowulf spawned. In fact, what we’ve done is gone back to the Norse roots of the story.

“In a way, we’re dealing with how the story came into being as much as we are with the story itself. It’s a re-imagining of the myth. “The basic question that we ask is ‘what if the hero was a complex, thinking man? And what if the monster wasn’t really a monster?”

Beowulf was at one time regarded as a simple monster story, an approach rebutted by J. R. R. Tolkien in his essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Sturla agrees, pointing to the saga tradition “which is really where this story comes out of — in those stories the characters are much more complex. The heroes are not all good and the villains are not all bad.”

Beowulf was at one time regarded as a simple monster story, an approach rebutted by J. R. R. Tolkien in his essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Sturla agrees, pointing to the saga tradition “which is really where this story comes out of — in those stories the characters are much more complex. The heroes are not all good and the villains are not all bad.”

The film is also not going to be replete with computer-generated special effects. “There’s no visual effects in this movie,” Gunnarsson says. “We’re going back to pre-Jurassic Park filmmaking.” Though they will use prosthetics and makeup, he says, “it’s all being done with real actors and real action bound by the laws of gravity. Same with the fighting — it’s all very historically rooted. Those big broadswords are pretty amazing, and you don’t swing them easily. The idea was do something where the action of the piece feels very, very real.”

Aside from his desire to shoot a movie in Iceland, Sturla says,“On a certain level — spiritually, I think the film lives in Iceland more than anywhere else.”

He adds that film production is proportionately high in Iceland (six or seven movies a year in a country of 300,000). “Also, it’s just such a phenomenal landscape,” he says. “It’s a landscape that’s never been seen on film, certainly not in any kind of a mass-market film. I mean [James] Bond has shot there, and Lara Croft shot there, but they sort of represent three or four minutes in the films. This is a film that lives and breathes entirely on that landscape. It’s elemental, it’s primordial — it hasn’t changed in a thousand years.”

He admits it’s a challenge to film in the famously expensive country — he jokes that “you have to search long and hard to find a place that makes London look cheap” — but that drawing from local talent, and using a slightly smaller crew, helps.

He admits it’s a challenge to film in the famously expensive country — he jokes that “you have to search long and hard to find a place that makes London look cheap” — but that drawing from local talent, and using a slightly smaller crew, helps.

Costs are also offset by having an Icelandic co-producer in Fridrik Thor Fridrikson. “Icelandic Film Fund has invested,”says Sturla; “there are tax incentives, and there’s also an equity investment through the Innovation Fund. It’s a bit of a pilot project for Iceland, actually… they’ve been participants now for nine months in helping us make the financing work.” Filming will begin August 30 and is scheduled to last 10 weeks, for the most part in Höfn and Vík.

Written by David Jón Fuller Winnipeg, MB